Jean-Manuel Izaret leads BCG’s Marketing, Sales & Pricing practice globally. They partner with leading companies across industries to transform their commercial functions leveraging cutting edge digital and analytics capabilities to help them grow.

In this episode, Jean-Manuel reveals the impact of your pricing models on maximizing your pricing strategy.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Why you have to check out today’s podcast:

- Explore the factors behind the fluctuating gasoline prices, where price rises easily when the market is up, and takes time lowering when the market is down

- Get an exclusive preview of the subjects discussed in the Game Changer book

- Discover what a ‘choice game’ is all about

“Think about how to share the value with the market and with others, you’ll bring long-term customers and loyalty, and you’ll build a fantastic business for yourself.”

– Jean-Manuel Izaret

Topics Covered:

01:36 – How he got into pricing

02:54 – Why gas price tends to go higher fast than it goes down

05:46 – Are gas price and other commodities coming back down

07:27 – What made him write the book and a sneak peak into the topics

12:29 – Important thoughts on value-based and cost pricing and identifying brands for illustration

20:29 – Relevance of elasticity in pricing

24:23 – His game of choice and why

26:45 – Industries that have huge advantage with value pricing

27:20 – Jean-Manuel’s best pricing advice

Key Takeaways:

“It is helpful for anybody in any market to think about the value that they create for customers. And never thinking about it is usually a mistake.” -Jean-Manuel Izaret

“Everywhere you are, think about what people on the other side are doing, and is it relevant for you? How can you learn from that?” – Jean-Manuel Izaret

“When people think about pricing, they tend to think about prices. They tend to think about the number. If you want to reframe the conversations about how you can gain more traction in the market, think about your pricing model.” – Jean-Manuel Izaret

People/Resources Mentioned:

- Game Changer: https://www.amazon.com/Game-Changer-Strategic-Pricing-Business/dp/1394190581

- Shell: https://www.shell.comNetflix:https://www.netflix.com/ph-en/

- Apple: https://www.apple.com

- Napster: https://www.napster.com/availability

- Sony: https://www.sony.com/en/

Connect with Jean-Manuel Izaret:

- LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/izaret/

- Email: [email protected]

Connect with Mark Stiving:

- LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/stiving/

- Email: [email protected]

Full Interview Transcript

(Note: This transcript was created with an AI transcription service. Please forgive any transcription or grammatical errors. We probably sounded better in real life.)

Jean-Manuel Izaret

Think about how to share the value with the market and with others, you’ll bring long-term customers and loyalty, and you’ll build a fantastic business for yourself.

[Intro]

Mark Stiving

Today’s podcast is sponsored by Jennings Executive Search. I had a great conversation with John Jennings about the skills needed in different pricing roles. He and I think a lot alike. If you’re looking for a new pricing role, or if you’re trying to hire just the right pricing person, I strongly suggest you reach out to Jennings Executive Search. They specialize in placing pricing people. Say that three times fast.

Mark Stiving

Welcome to Impact Pricing, the podcast where we discuss pricing, value, and the unique relationship between them. I’m Mark Stiving, and our guest today is Jean-Manuel Izaret, otherwise known as JMI. From here on out, here are three things you want to know about JMI before we start. He has been a consultant with BCG Boston Consulting Group for over 26 years. He is the co-author of the new book Game Changer, and he loves to teach math. So any kid seven to 17 who visits his house in Tahoe has to do math. Welcome, Jean-Manuel.

Jean-Manuel Izaret

Thank you very much, Mark.

Mark Stiving

So how did you get into pricing?

Jean-Manuel Izaret

I got into pricing in a very simple way. I started to work at Shell, and after a couple of years, I ended up working on the pricing of service stations because the guy on the other side of the office was doing this. And I tried to help out. That’s one way. but more broadly, pretty quickly, going out of Shell. I knew I wanted to become a consultant and I also learned that I didn’t want to work on costs. And so I did two things. One is I moved toBerkeley to follow my wife who was doing her MBA there. but working in Silicon Valley was a way to be sure I would always work on growth and never on costs. And then within that, I chose to focus on pricing, which I had a little bit of experience and a starting point with pricing the pure commodity that gas is, gasoline and then starting to learn how to price lots of other things like software and technology products and many more. And then I never left.

Mark Stiving

Nice. Okay. I wasn’t expecting to ask you this, but since you worked at Shell, I have to ask this. Give me your explanation for why the price of gas at the pump goes up the day the price of oil goes up, and as the price of oil goes down, the price at the pump goes down slowly.

Jean-Manuel Izaret

It’s the typical asymmetry of the people who do pricing on gasoline. No, they don’t have that much to play with. You could play with different elasticity in different stations, but it’s quite complicated and so on. The obvious is you play with time and overtime as soon as you have a pretext to bring your prices up, and if you know your competitors will do exactly the same thing and push their prices up, customers will not have a choice. And it’s not like people can decide to not drive their truck to work in the morning. They will have to, and no matter what, they will do that. And then on the other side is the asymmetry. Try to keep it as high as possible for as long as possible and to keep your margins up. And the fact that, again, you have at a local level, not that much competition, usually, you price with three or four stations around your station means that you could observe what they do and you could retaliate to stations that don’t play well, let’s say the game. And it’s a very micro game that everybody plays. And that’s what I observed at the time. And, since you observe the same facts that’s going on everywhere in the world.

Mark Stiving

Yeah. So that’s essentially the explanation I always give, that when it goes up that price of oil going up is a signal to everybody to say, hey, let’s go raise prices. And, then as it comes down, it’s competitive pressures that are driving it down, but that’s much more slow.

Jean-Manuel Izaret

That’s right. And I think we could draw a parallel to what happened at the end of COVID and the inflation time that we’ve been to, maybe like me and many others, you have observed that often companies have a tendency to overestimate elasticity. In other words, to think they will lose a lot of volume if they push the prices up more than what the reality is actually. which means on average, many companies tend to price slightly under where the optimum is. But when COVID hit, we had two things hitting simultaneously. First a microeconomic shock with less supply of many products. And so one that pushed the prices up, but I think the price increase we got, and so the inflation we got surprised many economists because the price increase was more than just what the cost shock would have cost, would have driven. And it’s because everybody realized they could push the prices up without worrying too much because their competitor was also pushing the price up. And that’s sort of what we’ve seen with a burst of inflation that surprised everybody the first time in 20, 25 years, 30 years is exactly the same effect that you highlighted in your forecast nations.

Mark Stiving

Very interesting. And so do you think that prices will actually come back down, or do you think they’re going to stay where they are and maybe go up at the 2% inflation rates we’ve always seen historically?

Jean-Manuel Izaret

I think we’ll get back to the 2%, 2.5% historical inflation rate that everybody’s used to. But I think the pattern is really dependent on the type, what we call the type of game in the book that an industry can find themselves. So it’s not the same answer everywhere. So we’ve already seen that for what we call the cost game, where you price cost-plus, or the dynamic game where you have a lot of fluctuations of time and so on, these prices have adapted and come back down. All prices have come back down until, of course, we have the war in the Middle East, and then suddenly they go back up. But all prices, food prices have come up and down for commoditized products. but on the other side, the price of watches and high-end pianos went up faster, and that’s it.

They’re not going to go back down because they are priced to value and they take a share of the value. Customers at the high end of the markets have actually quite a bit of willingness to pay and continue to do well during the pandemic and after. And so therefore, the pressure to bring these prices down’s less. For some markets we go back to some prices down, and we’ve seen this already, partially you’ve seen it in supermarkets with a bunch of supermarket chains committed to pulling the prices back down. but you have a lot of other markets. I just talked about luxury items, but you can think about subscriptions as well, Netflix and so on. I don’t believe these prices are going to go down. And we can talk in more detail about why there are different games and therefore they have different behaviors.

Mark Stiving

Okay. So since you brought up the word game and the title of your book is Game Changer, tell first off, why’d you write the book and, and give me a big overview on what it’s about?

Jean-Manuel Izaret

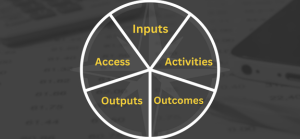

I wrote the book because over the years I found that the largest impact of pricing changes was not about changing prices, but was about changing price structures and pricing models. And I thought there was not enough written about pricing models. What you could find is a list of books and articles thinking, oh, look at this list of eight pricing models. And a new one would say, oh, there are actually 10 pricing models and you can pay as you go and subscription, and good, better, best, and all of that. And I wanted to try to bring some order and a framework that allows people to make these pricing model choices in a better way. And to do that, I came back to the fundamentals of pricing which is you make every pricing decision with cost-value and what competitors are doing in mind.

And then you have the intersections between, sometimes you combine information, cost information and value information. And that’s what elasticity allows you to do. And sometimes you combine cost and competition, and that’s what game theory allows you to do. And sometimes you combine what value and what competition tells you, and that’s what behavioral science tells you to do. And if you combine everything is roughly the supply demand framework that we all know and love. So I just went with a simple, starting with three different sources of information, they intersect with three different frameworks that we all use depending on the time. and in the middle is a supply demand framework, and that gives you seven positions. and maybe I should show it with, with my fingers, with just seven fingers. But that seven positions of these Venn diagrams with three things intersecting, they actually correspond to different pricing methods.

You could price just based on your costs. You could price just based on the elasticity. You could price just based on where your competitors are, et cetera. Or you can price based on a combination. And so this combination of sources of info and methods about how to do pricing actually fit within this Venn diagram I described. And as I discovered over the last 15 years, playing with this framework a little bit, you actually have different market characteristics that drive you to price a different way. In other words, when can you price to value? Well, usually you tend to have a very differentiated product that there’s not that many competitors. So you have one main competitor, a lot of customers, one very differentiated product. It’s the opposite to when you are forced to price to cost, you’re forced to price to cost if your product is not differentiated, if you have a lot of competitors that all do exactly the same thing.

And you have very super powerful buyers that buy a lot and will push your prices down the cost. So it’s the opposite of what I call the value game. And so when you go around the Venn diagram, you find that you have different market characteristics, whether on the differentiation of your product, the concentrations of your buyers, and the concentration of the sellers that determine what game you play. And so the book is an exploration of all these games. What characterizes them, what is the best way to win in these games, and then also when is it relevant to think about how to change games from one to the other? Could people that are customers and competitors that are in the cost game, can they move to the value game? Is it possible for anybody to price to value? How do you move from one place to another? So the entire book is about exploring these games as a general framework, simplifying the math into what the market is like, and then helping people make simpler decisions. Because you don’t have to consider, all the time, every single type of framework economics that you could look at. and you can just be more focused on, in my industry today, this is the game I’m playing, this is how I will win.

Mark Stiving

Okay. I have to say that I love that explanation. And by the way, I’m looking at the chart right now while we’re talking. And I love the explanation because it forces me to think really hard, but I do want to push back. I personally always teach value-based pricing, always. Without exception. And I define value as charging what a customer is willing to pay. And so now when I look through your chart and I say, I’m Shell and I’m pricing gasoline, right? Obviously cost drives a lot of what’s happening, but what’s really driving that is my competitor’s reactions. And so my customers get to choose between my product, my competitor’s product. And so what are they willing to pay for my product? Well, if I’m on the right hand side of the road, if I have a better brand name, they might pay 3 cents more than my competitors do. And so that to me is value-based pricing.

Jean-Manuel Izaret

Yes.

Mark Stiving

So I’d love to hear your explanation of that.

Jean-Manuel Izaret

You are right that it is helpful for everybody to think about the value they create and what their customers are willing to pay. So why do we tend to emphasize value more often? Well, because most people when you think about pricing, think about their costs. That’s what Aristotle started to… So the cost is a given. Everybody thinks about that cost. When they do a little research of their market, they think about their competitors and they look at what they do and where they are, what they could do and so on. So the most common item people look at is everybody looks at cost. Most people look at competition, and as an advisor for pricing, telling them, hey, think about the value that you create for your customers, is always a good way to help them rethink.

But how far you’re going to be able to go with that value logic depends a little bit on your circumstances. Sofor instance, when Apple comes out with the iPod, the advice to the product manager of Apple to think about the value they create with the iPod is really fundamental and helps them refrain, if they just look at competition, and all the MP3 players are priced around 100 bucks, between 80 bucks, 79, and 119. And Apple basically puts a hard list drive in it that allows you to have more songs. So 200 songs instead of 20. if you don’t think too much about the value, and you know that the little hard drive costs you 40 bucks, you think, ah I could go between $100, which is the average price plus 40, which is my margins are less, but I have the same in percentage I have the same amount or maximum 200 bucks.

And that’s where you think, and where does Apple come out? Apple comes at 500, 499, I think the firstiPod and around 400 bucks for a while. And not only did it come out at a much higher price point than anybody imagined, but they took over the market in three years. Illustration of your point, you think about the value creatively, and suddenly you can unleash a lot of productivity, a lot of value for you, your customers, you can gain the market and so on. Now, the question is, could everybody do that? What allowed Apple to do this in ways that other people could not necessarily do? Think about a startup coming out with new MP3 players with this idea of putting a hard disk drive in it. WellSteve Jobs went to the music industry and told them, you’re going to stop bundling these albums altogether, and you’re going to unbundle the whole thing.

And if you don’t do that, you’re not going to have a business anyway, because Napster is going to take over. so I’m going to help you, but you need to help me. And these are the conditions. He also told them, and by the way, the price of all your songs is going to go to a very simple 99 cents per song, and I don’t want to hear people like, there’s songs that are better than the other, blah, blah, blah. Like, make it simple, right? and so not everybody could do that. And at the same time, he put $300 million of advertising at the launch that even Sony, who owned the Music Walker space by inventing the cassette just 30 years ago, was not ready to spend. And so the condition for Apple to be successful with the iPod was to align a number of things in the ecosystem and to offer the entire experience of the solution, which was really hard for others to do.

And so I think it is helpful for anybody in any market to think about the value that they create for customers. And never thinking about it is usually a mistake. Now, how much you’re going to be able to extract also depends on the necessity of your value proposition. the level of competition you have the concentration of your customers. If you have just two customers it’s going to be very different than if you have millions of customers. And so that combination is something that leads you to the other games. And just to take the asymmetricperspectiveI would always advise people that are in the pure value game and think value is the only thing to think about. What is competition doing? It’s always relevant for them. And thinking a little bit about game theory for people that are in the luxury items and selling perfumes and say, I do not care about competition because my product is so much better. Look at this magnificent advertising that I had. Well, just look at what they’re doing. Maybe you could learn something and maybe you’ll find some inspiration about how they go to market and how they advertise or promote, or what else you have. Always something to learn from other sides of this Venn diagram I was talking about. Everywhere you are, think about what people on the other side are doing, and is it relevant for you? How can you learn from that?

Mark Stiving

Yep. Couple of thoughts. First off, agree a hundred percent. Although I always teach value-based pricing, costs matter in some ways. Competitors matter in some ways. So we always have to think about those things. And we have to think about value. As you told the iPod story, I had a realization that I’d never had before, which I thought was kind of funny. So Steve Jobs prices the iPod based on value but he forces the music industry to not.

Jean-Manuel Izaret

Yes, that’s right. That’s exactly right. So he changes the game for the music industry and takes over. but if you think about how value has been extracted from, like, the willingness to pay for consumers of music is roughly the same today as a proportion of their income as it was 50 years ago. But 50 years ago most of the value was extracted by some people that were music fans buying a lot of records. And that’s where the spend was varying. And the spend on the devices were pretty fixed. and we got to the other side, right? and the value, a lot of the value has been extracted by the devices. Think about how some headphones are now at 500 bucks a piece because they’re so good and so on. Why are the headphones so expensive? Well, it’s because the music is not expensive, and you have the same willingness to pay overall for the music experience. At least that’s my interpretation. And we have also seen that in the music industry, you have in the music production industry, essentially a lot more money went into concerts and live performances than was the case in the eighties and nineties because people have adapted to the changing ecosystem. But the willingness to pay the average spend per consumer and for the fans is roughly the same as the percentage of your income as it was30 years ago. It’s just shifted where the spend was.

Mark Stiving

Yeah. I think that’s pretty interesting. And some people who love music have a certain size of their budget they’re willing to spend. So where are we going to spend it? Yes, that’s right. And if it’s not buying albums and going to concerts, it’s headsets. Yeah. It also used to be really expensive speakers.

Jean-Manuel Izaret

Yes, that’s right. And then, and then suddenly it was hard to connect the speakers to the internet. And then for a while the speaker market went down in terms of margin and so on. So yes, that’s right.

Mark Stiving

Nice. I have so many things or so many directions I could take this. Let me ask you about elasticity, which is one of my least favorite topics. And it’s really interesting the way you have it in your chart. you identify exactly why it’s my least favorite topic, and that is that it ignores competition. And so if someone uses elasticity and says, oh, look, it’s highly elastic. I should lower my price so I can gain more shares. Well, what’s the competitor going to do? And we just ignored that. So I tend to tell people not to do elasticity, but I would love to hear your thoughts about that.

Jean-Manuel Izaret

Okay. I also first discovered myself that elasticity was very often completely irrelevant, and I can tell some more stories, but just to build a little bit on, people tend to overestimate the importance of elasticity. And for most markets it is not as important. So let me talk about when it is important. When can you ignore what competition is doing? Well, if you have a market with, let’s say, 20 competitors, all with roughly the same product, but not exactly the same products. Can you price into a lot of different stores everywhere around the country and so on, can you track where the prices of every single one of your competitors on every single product? It’s really impossible. And on average, the competitors are going to roughly, if you are in a mature market, the prices have roughly converged and they’re roughly in the same place.

So they’re slightly above, slightly lower, but the average of what customers are willing to pay is roughly the same. At that point elasticity could be relevant for you. If you are a small player in this very fragmented market, that’s the only place when I think elasticity can matter because the competitors don’t react to you because you are really small. Like you won 20th of the markets, like nobody sees you and so on. And the same way, you don’t see them, they don’t see you and everybody prices roughly. And so the way to get feedback about the market is, well, each competitor moves their prices a little bit up and down. They observe their volume and their resulting margins going up and down, and they optimize that. That’s the situation. As soon as you have less competitors, suddenly you could start to track what they do.

As soon as you have one to three competitors that are much bigger than others, have more influence on the market, then everybody looks at them. You can’t afford to not look at them. And therefore elasticity becomes irrelevant because you need to take into account the game theory aspect of things that you just mentioned when you look at what competitors are doing. And by the way, value also matters. And instead of just saying, oh, this is where my product is and I’m just going to move my price. If you think about it, well, what do my customers want? Can I change my product to get something that my customers might want more? Can I differentiate myself? Can I go in niches and so on? Suddenly, when you are in a niche, your niche is closer to being yours, to be you.

More importantly, you have more concentration of your less competitors. And suddenly elasticity again, doesn’t matter anymore. And then if you were to be in a market where you are in the B2B space and you give different prices to every single customer, then suddenly elasticity doesn’t matter. Because what matters is the willingness to pay and the value equation of every single customer and the aggregate where everybody pays the same price is not relevant anymore. So you have so many market situations that make it such that elasticity doesn’t matter as much, but there is, with the right combination of market structure, competition and so on, I think in that particular place, it matters and it’s helpful to know the concepts and to be able to play with it.

Mark Stiving

Okay. I think that’s a very fair answer. I’ve always realized that elasticity was good for industries, right? Economists use it for industries all the time, and it makes sense. And so if you essentially have a monopoly, elasticity makes sense for you. If you have no competitors, but the thing you just taught me, which I’m thrilled that I learned something new, is that if you are a tiny, tiny fish in a big pond, no one’s going to respond to you. So it doesn’t matter. You can use elasticity.

Jean-Manuel Izaret

That’s right.

Mark Stiving

And that’s another use case that I find valuable. Thank you. Okay. So what’s your favorite of the games?

Jean-Manuel Izaret

My favorite is the choice game. You want two offers for choices. So the choice game is the game that is at the intersection of competition and value. It’s one that says cost doesn’t matter anymore. If you look at how the economy has evolved, a lot of the innovation over the past 20 years has happened in markets where the marginal costs are either small or negligible, and therefore they don’t matter. When you are in that space and you still have significant competition, you can’t afford to price to value and not worry about competition. You need to think about how to frame the choices for your customers. and you have a lot of ways to do that. It requires a deep understanding of the customers, segmenting them really well, finding the right things, letting your customers self-select to where you’re going to price.

You can’t price based on costs because the costs are not there anymore. So an example of that industry is the software industry. And if in the software industry that has so many upfront costs, you start to have a product that is different for every single customer then the development costs and the maintenance costs get so much in fixed costs that you can’t have a business anymore. And so, for instance, the software industry needed to price with a choice game, but it’s not the only industry that does not think about, you know. Starbucks, when you walk into a Starbucks store you will have choices between coffees. If one of them, the extra latte with pumpkin spice thing and so on. You think it’s too expensive, you’re going to need something less expensive, but it will still be in Starbucks. You won’t walk out. You came in with friends, you have choices. And I think behavioral science is the art of framing choices for customers is varied, complicated, interesting, all terms of all types of situations that have different answers. And that’s both fun and can create a lot of value for people who play that well. And that’s therefore my preferred game.

Mark Stiving

Nice. I often think software companies or data companies have this huge advantage that they don’t have hard costs because then they have no choice. They have to price on value otherwise they’d be pricing at zero.

Jean-Manuel Izaret

Yes, you’re exactly right. but that’s also not true only for these data services or software industries. It’s mostly true for the healthcare industry when it comes to pharmaceutical products. Drugs, the cost of producing drugs is minimal when you bring it in comparison to the cost of developing the drugs.

Mark Stiving

Yeah. JMI, we are going to have to wrap this up but I’m going to ask the final question. I always ask, what is one piece of pricing advice you would give our listeners that you think could have a big impact on their business?

Jean-Manuel Izaret

That we haven’t talked about before? I’m going to try to keep it simple. When people think about pricing, they tend to think about prices they tend to think about the number. If you want to reframe the conversations about how you can gain more traction in the market, think about your pricing model. Think about the unit by which you price. Think about the way you package the choices for your customers. Think about things that come before you come to the price. Reframe the conversation. Don’t go right to, what’s the number. Go to, how do we think about how we exchange value with our customers? And the results of, if you do that, you’ll spend more time thinking about how you should share value, how much value does it deserve, as opposed to extracting the value, which is the word I hate about, I love the word value, I hate the word extracting. Think about how to share the value with the market and with others, you’ll bring long-term customers and loyalty, and you’ll build a fantastic business for yourself.

Mark Stiving

Nice. Thank you so much. And by the way, I agree completely. The number itself is not as important as the structure. Oh my gosh. Thank you so much for your time today. If anybody wants to contact you, how can they do that?

Jean-Manuel Izaret

I’m pretty accessible on LinkedIn, but if you want to send me an email, it’s pretty simple, email at [email protected].

Mark Stiving

That has to be the shortest email address I’ve ever heard. Nice. To our listeners, thank you for your time today. If you enjoyed this, would you please leave us a rating and a review? And if you have any questions or comments about the podcast or pricing, feel free to email me, [email protected]. Now, go make an impact!

Mark Stiving

Thanks again to Jennings Executive Search for sponsoring our podcast. If you’re looking to hire someone in pricing, I suggest you contact someone who knows pricing people contact Jennings Executive Search.