Robert Edwards specializes in delivering consulting and training for company executives to understand how to optimally price their products and services, monetize their products, maximize value generation and extraction from their product portfolio, and develop their promotions and competitive strategy to increase profit. He holds a PhD in Pricing and Competitive Strategy.

In this episode, Robert shares how to simplify your pricing and effectively communicate its benefits and what value it generates.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Why you have to check out today’s podcast:

- Understand how to use price to generate value for your product or services

- Learn to use pricing to attract the customers you want

- Find out about the connection between behavioral economics and pricing

“Creating value for your pricing could be an extra dimension to what we talk about regularly when we’re thinking about designing our products and pricing those products.”

– Robert Edwards

Topics Covered:

01:25 – How he found his route into pricing

03:15 – Discussing the idea about complicated and simple pricing

04:55 – How Ryanair creates a perception of simple pricing

05:55 – Why make your pricing simple

07:04 – Robert’s important thoughts on creating value for your pricing

08:48 – How to add value through pricing

10:42 – LinkedIn as an example in the way of creating value and not just extracting value

14:34 – Thinking in terms of the buyer composition and not just the number of units bought

16:35 – Examples that uses price to attract the customers you want

19:50 – An example that uses pricing as an attention grabber to make all else reasonable

21:09 – A case of sellers focusing on different dimensions in attracting customers and not just pricing

22:57 – How pricing and behavioral economics tie into each other

25:36 – Considering behavioral economics at the beginning rather than at the end of the pricing process

26:18 – Understanding the pricing strategy around rebates

27:01 – Using value-based pricing and having the clarity of message why you’re pricing in such a way

Key Takeaways:

“I would definitely recommend in a lot of cases simplifying your prices adds value to the products and service that you’re offering because consumers have a really strong preference for this as well.” – Robert Edwards

“Behavioral economics is increasingly at the heart of real pricing strategies because you can design a pricing strategy with rational consumers in mind, and it completely does not work the way you intended because consumers have these biases and they’re susceptible to framing effects.” – Robert Edwards

“A lot of the companies that I speak to, there’s an opportunity to add value to their product by using a different pricing metric. And the only reason that pricing metric is really valuable is because of the behavioral biases of the consumers.” – Robert Edwards

People / Resources Mentioned:

- Ryanair: https://www.ryanair.com/gb/en

- LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/

- Subway:https://www.subway.com/en-us

Connect with Robert Edwards:

- LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/edwardsra/

Connect with Mark Stiving:

- LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/stiving/

- Email: [email protected]

Full Interview Transcript

(Note: This transcript was created with an AI transcription service. Please forgive any transcription or grammatical errors. We probably sounded better in real life.)

Robert Edwards

Creating value for your pricing could be an extra dimension to what we already talk about really regularly when we’re thinking about designing our products and pricing those products.

[Intro]

Mark Stiving

Welcome to Impact Pricing, the podcast where we discuss pricing, value, and the multi-directional relationship between them. I’m Mark Stiving and our guest today is Robert Edwards. And here are three things you want to know about Robert before we start. He is a professor at the University of Nottingham. They cut down the trees that, oh my God, what was the sheriff of Nottingham was in to build that university. He has a dissertation. His dissertation was on, when companies complicate pricing and when they simplify pricing. And I’m going to say, I find that an absolutely fascinating topic. We might get a chance to talk about that a little bit today. And he competes in HYROX competitions. I have no idea what that really means. I’m going to look that up after the podcast and just by looking at him, I can tell you he’s in amazing shape. Welcome Robert.

Robert Edwards

Fantastic to be here. Thanks for having me, Mark.

Mark Stiving

Hey, it’s going to be fun. How did you get into pricing?

Robert Edwards

So, for me, kind of as you alluded to, I’ve stayed in an academic setting for quite a few years. So initially my route into pricing was when I was finishing my master’s thesis and I was looking for a topic that I was really interested in that I wanted to study as part of my PhD. And I’m an economist by training. And one of the key topics that jumped out at me was, on the one hand you have all of these economic models of price optimization that generally assume everyone in the market is fairly rational. And then on the other side, you’ve got this whole literature on behavioral economics saying not everybody does behave rationally. And what I was interested in really is how you could optimize prices, given that we all have biases. And I think my personal route into pricing as well before I started this in an academic context is I was just a consumer in a situation where I was looking at all these different prices and I kind of backward engineered some of the pricing models companies were using for my own benefit as a consumer. And before I knew it at university, other friends, and family were getting me to do the same for them. And that was kind of my route into actually being interested in pricing. And the final part to do with my thesis was back in 2014 when I was doing my PhD. As you mentioned, there was a big push around regulation in the UK and also in the EU around what it means to have complicated pricing and how we can use policy to simplify the prices that consumers receive.

Mark Stiving

Okay. Well, since it’s not going to be our main topic, but since we brought it up, let’s just talk about it for a brief moment. By the way, I like your dissertation topic more than I like mine. And now, by the way, mine was a cuter topic. It was 99 cents, but yours seems to be way more impactful than mine does. But here’s my question. Can you give a quick summary on when companies want to have complicated pricing and when they want to have simplified pricing?

Robert Edwards

So the main idea if we go about 10 years ago was we’d reach a point where complicated pricing would become the norm in a lot of markets. So if you think about a lot of B2C markets, I’m thinking domestic utilities, your energy, your gas, your mobile phone, your broadband, these are products that you have to buy. And the idea is that some companies were deliberately creating complexity around their prices to make it difficult for consumers to compare. And that was leading to higher prices. So that was the real incentive for making prices complicated. The flip side on the simplification is what I actually studied as part of my PhD, which said, okay, given that all the other companies in the market are doing this, is there an opportunity for a firm to simplify their pricing because consumers have biases towards those simple prices and they’d actually be rewarded for doing that. So that was one of the focuses of my PhD.

And it does pay to simplify your prices. So I can give you budget airlines in the UK. So Ryanair advertised the low fares made simple. We’ve seen retail banks with savings made simple and a whole range of firms over the last eight or nine years that have really pushed the simplicity of their products. On the one hand, you could say it’s advertising that they’re simple. The real question is, are they simple to compare? Because that’s what really matters for consumers. But there’s a definite incentive for firms to simplify their pricing if consumers are biased towards simple pricing.

Mark Stiving

Yeah. So I would have argued that Ryanair has complicated pricing. And I say that from the sense that it’s more of an a la carte pricing scheme where I teach companies all the time, look, try to do good, better, best pricing because it’s just simple pricing for customers to understand.

Robert Edwards

Yeah, absolutely. And I think there’s also then how you perceive simplicity. So Ryanair, as you say, has really complicated prices. You break down the ticket, the bag, the seat, all these factors. So that initially could put a lot of consumers off. So what they’ve tried to do is convince consumers that they have low fares made simple so that consumers don’t instinctively think it’s too complicated to deal with that particular company.

Mark Stiving

Nice. So I think I agree with everything you said. When I was studying cell phone companies or at least looking at the prices and the way they do it, it seemed to me that they complicated the heck out of it. The reason they do it is because there’s not a lot of differentiation and they need a way to make it hard to compare, make it hard to say, yeah, this is better than that one so they can keep their customers. I think in places where there is a lot of differentiation, then it makes a lot more sense to say, look, I want to keep this really simple. I want people to be able to choose because hey, confused buyers don’t buy.

Robert Edwards

Yeah, absolutely. And I think that’s a key distinction as well. If the customer has to buy your product, so we have to buy broadband, we have to buy electricity, those firms are much more likely to use complexity compared to a company trying to sell you a product where if you’re confused, you choose not to buy. So there’s a separation maybe there between products where you have to choose one and then other products where you don’t necessarily have to choose one. And there’s a difference there as well.

Mark Stiving

Yeah, I think that makes a lot of sense. And so most of our listeners are probably not on utilities or cell phones . So, my recommendation is try to figure out how to simplify your pricing. That’s what I always teach anyway. But, I would guess you didn’t object too much to that.

Robert Edwards

No, absolutely. So I would definitely recommend in a lot of cases simplifying your prices adds value to the products and service that you’re offering because consumers have a really strong preference for this as well.

Mark Stiving

Yeah. Great. Well great segue for me. Thank you. Because what we really wanted to talk about today was how can we create value through pricing? And I have a whole bunch of thoughts on this, but I’m just going to toss you the softball cause I want to hear what you were thinking when you said, hey, let’s talk about this.

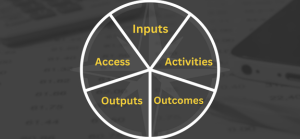

Robert Edwards

Yeah. So I think creating value for your pricing could be an extra dimension to what we already talk about really regularly when we’re thinking about designing our products and pricing those products. So for me, there’s two real steps when we’re pricing. The first one is to design a product or a service that is actually valuable for our buyers and have a really clear value proposition that communicates effectively what that product is going to do. And then on the other side, in terms of our pricing, we want to align our whole pricing scheme to the value proposition that we’ve created to extract the value effectively. So we want to think about things like using appropriate segmentation, choosing the appropriate pricing metric, using appropriate framing, and bundling. All of these factors are designed to extract the value that you’ve already created in the products or services that you designed. So my idea here that I wanted to discuss with you is, can we use prices themselves to actually create value for our products and services? And one of those could be to actually have simple pricing that could add value because consumers value simplicity. Or I’ll just give you a really quick example of…

Mark Stiving

Pause one second, Robert because I want to ask this, I just want to make sure I’m on the right page. So you said, hey, we want to use value to figure out what products to build. Hey, we want to use value to figure out how we’re going to do pricing and what the pricing strategies and tactics might look like. But those two aren’t what you’re talking about when you say we’re going to add value through pricing and we’re now going to say here are some ways to think about adding value through pricing. I just want to make sure everybody else was on the same page and that I understood what you were saying correctly.

Robert Edwards

Yeah, absolutely. So it’s kind of an extra dimension to bear in mind as we go through that process.

Mark Stiving

Beautiful. Let’s hear them. Well, we heard simplified pricing.

Robert Edwards

So it could also be, I’ll give you a quick example. Imagine you set the prices for the rent in a shopping center. So generally you’ll have different retailers within that shopping center. You might have the large, big brand names and they take a large store, they essentially get a lot of value and profit from being in your shopping center. On the other hand, you might have a smaller store, they’re not going to get the same footfall through their store, they’re not going to make the same sales, they get a lower value from your shopping center. So in that sense, if you’re pricing the rent, you would think that the large, large store has to pay a higher price than the smaller store. But when we think about what shopping centers actually want to do, they want to encourage consumers to actually go to that shopping center because that generates the value that translates into the rents that the stores are willing to pay. And imagine you’ve got a really key anchoring store who draws all those consumers in. Yes, they benefit from having really high profit potentially from your location, but they generate value by attracting consumers to your shopping center. And that inflates the prices you can then charge to all of the other stores as well.

Mark Stiving

Yes. And so I would think of that as a loss leader strategy, essentially. How do I sell something to one person or how do I sell one thing to get them in the door and then sell more stuff at a higher price? So yeah I think that would definitely be a way that we could use price to help drive the value because we’re offering a low price to people who are generating value.

Robert Edwards

Yeah, I think it’s about understanding what’s generating the value for all of your stakeholders as well. So the consumers on one side and the retailers, maybe if I talk you through the example of LinkedIn that do this really effectively and it’ll really help to separate between extracting value and creating value, if that’s okay?

Mark Stiving

Yep. Believe it or not, I can picture it in my mind already, but please do this because I want to hear your thoughts.

Robert Edwards

So the way everyone generally focuses on LinkedIn is on the prices that they charge to the users. So the job hunters or the recruiters, and essentially it’s a textbook example of segmentation and aligning the value that all the users get with the prices they pay. There’s an extra layer of pricing on LinkedIn that doesn’t get focused on and that is the price of advertising space. So essentially what LinkedIn does is they decide we’re going to allow, let’s say 10% of our screen space towards advertising. Now, I would say that’s a product design decision that’s still making sure that consumers aren’t annoyed because we’ve got too much advertising. So it sits within creating a valuable product. But now what I want to think about is how should we price that advertising? So the way LinkedIn does this is they use a second price auction. So let’s suppose I’m an advertiser, I get to choose that I send an advert to everyone with pricing in their job title, they’ve segmented that area of the market.

And now I enter an auction against all of the other advertisers who want to advertise to these individuals and we compete in a second price auction. The reason being, then we all have an incentive to bid our true value because we know we only have to pay the second highest bid price. So there’s no incentive for me to try and pretend it’s not worth as much as it actually is. That I would say is extracting value. The part about creating value is how it’s not always the winner of the auction who bids the highest price that wins. Instead on LinkedIn the way it works is all of the advertisers are given a relevancy score and essentially the winner of this auction is the company with the highest price that they bid multiplied by the relevancy score. So what that means is if their advertising is really engaging and really interesting to consumers, they can win that auction even if they don’t bid the highest price.

So what LinkedIn is trying to do is to make sure that the advertisers really have an incentive to provide engaging content which benefits the whole ecosystem. And the final layer of incentive on LinkedIn is the price that you pay isn’t even just the second highest price that’s bid, it’s divided by your own relevancy score. So that means that the price that you pay kind of has a reducing effect, the more relevant your advertising is, and that benefits the consumers and all the users on the platform from having better content. And it also has this beneficial effect to the wider ecosystem on LinkedIn. So that I would say is creating value, not just extracting it.

Mark Stiving

Yeah. So I actually love that example. So what LinkedIn, just thinking about it from your perspective and my perspective. So LinkedIn, what they really care about is engagement on the platform. So they’re not focused on time on the platform or anything else. They’re focused on engagement on the platform. And what you just said was LinkedIn put together a pricing strategy so that even in their advertising world, they’re really still focusing on engagement on the platform. And so they’ve created a pricing strategy so that the companies who do a better job at engagement get a better price or are more likely to win the deal. So I think that’s a great example of how you can use price to drive value.

Robert Edwards

Yeah. And we tend to see this on other platforms as well. So Google for instance, has a similar mechanism and they actually have a lower bound threshold that says if your advertising isn’t this high enough in quality, it doesn’t get to compete in the auction. So they’ve got that lower bound threshold that even if you bid a really high price because of the knock on effect that you have on Google in terms of their advertising quality, you still won’t be shown to the consumers.

Mark Stiving

Yep, that makes sense. That makes a lot of sense. Okay. Any other brilliant ways that we can use price to add value?

Robert Edwards

I think a slight segue is to how we can think about how the composition of our buyers actually matters rather than just selling an additional unit. So what I mean by that in terms of value is, let’s go back to a classic example that we tend to see on the pricing of computer printers and ink. It’s a classic example where the printer itself is really cheap to lure the consumers into buying the item. And then when it comes to the ink, they’re generally much more expensive. So the textbook example of that kind of loss leader that we talked about, but what research has demonstrated actually is you don’t necessarily want to be the cheapest firm on the price of the printer, the reason being that there’s a composition effect in terms of who’s buying your printer. So if I’m the cheapest printer in the store, It’ll attract a disproportionately large amount of consumers who are really price sensitive and those consumers are much less likely to then go on to buy my profitable add-ons later on. So there’s an effect here where we need to think about the composition of the buyers that we’re attracting beyond just attracting the simple number of however many we can.

Mark Stiving

Okay. I think that’s again a really, really smart, brilliant observation. So essentially what you’re saying is there’s a set of consumers out there who are willing to refill ink cartridges, we’ll say. And so if I’m the super price sensitive buyer, I buy the least expensive printer I can find, and I’m also the guy who’s going to be refilling my ink cartridge. Whereas if I don’t buy, if I’m not that price sensitive as a general rule, I’m probably not buying the cheapest printer and I am not refilling printer cartridges. That’s pretty interesting. So we can use price to say we want these customers, we don’t want these customers. And that makes more sense when we’re thinking about the lifetime value of the customer than when we’re thinking about the value of that one transaction.

Robert Edwards

Yeah, absolutely. To give you another example of where this kind of plays out, there was a study done a few years ago actually on a price comparison website. So a situation where you would expect that the incentive is to be the lowest price firm on that particular listing, and it was for computer memory chips. And what was happening in that situation is the consumer decides based on the low quality item, based on the price comparison website, and then as you click through, you get the option to upgrade to a better product later on. And what they found in that study is actually you don’t necessarily want to be the cheapest firm for the low quality product because if you are the cheapest firm, again, you attract all of the really price sensitive consumers that when they go through the upgrade process, they never upgrade to those high profit items. So actually it can be a benefit not to be the cheapest firm on the price comparison website once you take into account the composition of the buyers that you will attract.

Mark Stiving

Yeah, that makes a lot of sense. Excellent. Another one, you have more. How many of these do you have?

Robert Edwards

I tend to pick them up every so often. I just see, I told you I’m a consumer first looking at all these different pricing strategies.

Mark Stiving

Yeah, I’m exactly like that. When I see something unusual or weird, it’s like, okay, why does this make sense?

Robert Edwards

Yeah. So I think there are two benchmarks that I use.

Mark Stiving

Okay. So let me give you one that I love, if I may. And, you guys have Subway over there?

Robert Edwards

Absolutely.

Mark Stiving

Yeah. The restaurant. So a few years ago, Subway actually advertised $5 Footlongs. And I just thought that was fascinating because they made $5 the reason to go buy the footlong, right? It’s rare that you see price as the reason unless it’s going to be a super low price, but it’s a memorable price. It was easy to understand. So I I really liked that and I thought the fact that they were using $5 foot longs was a way to add value to their marketing to their advertising.

Robert Edwards

Yeah, definitely. I think for me, the way I think about it is not to say it replaces any of the value that we focus on creating for the products or extracting the price. It’s just an extra layer to bear in mind when we’re designing all of these strategies.

Mark Stiving

Yep, absolutely. Maybe I’ll run these by you really quickly. I don’t think I’ve ever talked about this on the podcast. , so I created the six steps to value-based pricing. Which was the six steps you want to go through when I’m trying to say what price am I going to set? And so it starts off with, what’s the next best alternative? If they don’t buy yours, what’s the price, the next best alternative? What’s the positive differentiation? What’s the negative differentiation? Let’s do the math, right? Or what’s the value of those things? And so it’s just logical stuff, right? Yeah. But what’s fascinating is you go through each one of those steps and you find out there’s a place where you can add value to the sale, right? So who’s the next best alternative? Well, if I could influence you to compare me to somebody who’s very expensive or very poor quality, or right now I’m adding value to my product because I’ve influenced who you are going to compare me to.

Robert Edwards

Yeah, absolutely. A similar kind of effect is when companies that I’ve spoken to use attention grabbers. So you’ve probably been into a restaurant where you’ve seen the price of the champagne or the wine, and there’s a really high price listing on that particular menu. The general reason, obviously it makes everything else feel much more reasonable, it also affects their brand. But imagine a situation where you’re walking past a whole street of restaurants, it catches your eye. And even though you’re not necessarily going to buy that particular product, the price has had an effect on whether you considered that particular seller in the first place.

Mark Stiving

Yeah, I think that’s a great example. And when you see something really high priced, you automatically assume that the seller has high quality. Even for the lower price things. Great observation. Let’s see, influence the price of the second best option. Can I influence your perception of the price of something? And so in the US we have Southwest Airlines, they advertise all the time. Bags fly free. And the whole point is, you’re going to pay for this if you go to America or Delta or another guy. It’s just a constant reminder of yeah, I want to influence your perception of the price of my competitor’s products.

Robert Edwards

Yeah, that’s really interesting. What you often see in some markets is obviously competitors focus on completely different dimensions when they’re trying to sell you those products. So in a product where there’s 10 different dimensions, one insurance company for instance, on home insurance might focus on one dimension, other insurers focus on a different dimension. Again, drawing back to the idea that we’re not all perfectly rational buyers, we don’t have perfect information. So playing to those kinds of biases when we’re making our decisions and actually understanding what the prices really are.

Mark Stiving

Yep. So these are fascinating. I enjoy all these. I think it’s really fun. I’m going to ask the question. You actually wrote this down and you talked about it a little bit briefly though. How do you think pricing and behavioral economics really fit in with each other?

Robert Edwards

So in my experience, the way I tend to approach pricing projects is starting off with a benchmark model of understanding what would happen if we have rational buyers and then straight away saying, how rational are our buyers in practice? And that’s going to make a difference depending on which market you’re operating in, generally there’s a difference between B2B and B2C in terms of having a professional buyer versus consumers. And then when we’re in a B2C environment, which consumers are we actually selling to? Because there’s going to be different pockets of consumers in the market. Which ones are we targeting and how do the biases actually play out in practice? But I’d say behavioral economics is increasingly at the heart of real pricing strategies because you can design a pricing strategy with rational consumers in mind, and it completely does not work the way you intended because consumers have these biases and they’re susceptible to framing effects. And I should say as well, it’s not just firms that need to understand the effect of behavioral economics, it’s also the regulators side as well. So sometimes when you see regulations introduced around pricing and they’re intended to improve competition or reduce prices in certain markets, they can often have the opposite effect simply because we’ve not taken into account the idea of these behavioral factors on the demand side.

Mark Stiving

Okay. I love it when I get to disagree with my guests, and by the way, I’m not going to disagree vehemently because I’m not a hundred percent sure I’m right, but I’m going to push back. I usually think of pricing as I want to do value-based pricing. So we’ll call it the rational side of pricing. I want to focus on the rational side of pricing, and then I tend to think of behavioral economics as the icing at the end. I don’t think of it as, I’m going to create a strategy around this now, by the way, I can give you an example where I teach exactly the opposite of that. But I tend to think of behavioral economics as what’s my communication strategy of my prices to my marketplace, but creating the pricing strategy, the pricing model that I’m going to use, I can’t think of a time, well, I can think of one time, but it’s almost always just the rational side. But by the way, here’s the irrational piece, right? If I teach companies to use good, better, best pricing all the time and there’s absolutely behavioral economics in that concept, but step back from that one concept and I don’t think behavioral economics is that powerful that I would build a strategy around it. So feel free to convince me that I’m wrong.

Robert Edwards

So a couple of things that jumped to my mind. The first part is around pricing metrics. So the way that you’re charging for a product. So a lot of the companies that I speak to, there’s an opportunity to add value to their product by using a different pricing metric. And the only reason that pricing metric is really valuable is because of the behavioral biases of the consumers. So they want to see the prices in a slightly different way. They would prefer to see the pricing scheme in that way, and therefore the behavioral side is right at the heart of the pricing system that you’re creating. So there’s an opportunity there to add value at the very beginning if you take into account the behavioral side of the consumers.

Mark Stiving

Okay. Touche, you win on that one. So what I’m teaching pricing metrics, one of the things I focus on besides the fact is what’s highly correlated with value is what do your consumers accept as a pricing metric. What do your buyers want to see? And that plays a big role. And I guess if buyers are going to be irrational about that, we still want to price that as long as it’s correlated with value.

Robert Edwards

Yes. The certain products now that we see are subscription prices, whereas traditionally they were just fixed, you buy a one-off fee and there’s a behavioral side in terms of actually understanding how consumers are going to respond when we shift that pricing metrics. So that’s where I’d say behavioral economics could come at the beginning rather than at the end to do with the framing and the presentation.

Mark Stiving

Okay. I now have to start a list of times where I care about behavioral economics, where I care about the irrational thinking of my customers early on in the cycle as opposed to just at the communications phase. Because most of what we see in behavioral economics happens at communications, happens at the framing piece. How am I going to frame this?

Robert Edwards

So if you were thinking about, say, a pricing strategy around rebates, for instance, so if you buy an electronics product and there’s a rebate, but you have to wait three months, would you say that that decision on the rebate is taken at the very end of designing and pricing the product? Or does it come earlier?

Mark Stiving

I would say that almost always comes at the end. I’m not saying that it couldn’t come earlier. Yeah. But it probably almost always comes at the end. I think most promotions the companies do are after the fact promotions, they’re not, hey, let’s build a product so that we can do these promotions.

Robert Edwards

Yeah.

Mark Stiving

We’ll just leave it at that. Awesome. Any other brilliant ideas or thoughts you had while we were talking?

Robert Edwards

I think the final thought that I’d say is for firms to consider also the regulatory side of pricing. So what we’re seeing at the moment in the UK is a big push towards value-based pricing in terms of firms having to justify the true value of their products and services to show that it’s not excessive or misleading. So for instance, in the UK there’s been a big push around deceptive pricing to do with sort of false countdown timers that say this sale ends in a day and then it never does. Or there’s a limited quantity. So I say that’s the area as well of my work that I’m starting to see more and more focus on regulators taking more of an interest in the way we’re framing and communicating these prices. I think it just reinforces coming back to value-based pricing and having a really clear message to our consumers as to why we’re pricing in the way that we are.

Mark Stiving

Yeah. And although I’m not a huge fan of regulation, I’m also not a huge fan of lying to our customers. And so if we’re truly going to do deceptive actions, deceptive behaviors, I think we ought to be called out on it all right. There should be somebody that says, hey, this is not acceptable.

Robert Edwards

Absolutely. And what we’re seeing through some key cases now is the market mechanism is actually rewarding firms who are simple, who are clear, who are transparent about their pricing. So it doesn’t always need to be a regulator intervening, firms can win themselves by following that approach.

Mark Stiving

Yeah. If only that were true all the time. My favorite, I guess I wouldn’t call it deceptive, but it’s pretty darn close. It’s pretty darn mean. And that is, a lot of companies, when you want to cancel a subscription, make it really difficult to cancel a subscription, uh, even though it’s super easy to sign up and get started. So I find that deceptive and painful and I think companies are not rewarded. I mean, I think they are rewarded for behaving that way. And so it’s like that’s going to take regulation to solve that problem, I think.

Robert Edwards

Yeah.

Mark Stiving

So Nice. Hey Robert, this has been a lot of fun. I love it anytime someone can convince me that I’m wrong on something. Thank you so much for your time today. If anybody wants to contact you, how can they do that?

Robert Edwards

LinkedIn is probably the best. Absolutely fine.

Mark Stiving

Okay. There’ll be a link in the show notes for your LinkedIn page. And to our listeners, thank you so much for your time today. If you enjoyed this, would you please leave us a rating and a review? This is the currency for podcasts, so it would be amazing if you would do that for us. You can get instructions by going to ratethispodcast.com/impactpricing. And finally, if you have any questions or comments about the podcast or pricing in general, feel free to email me [email protected]. Now, go make an impact!