You can listen to the full audio version of this blog we call — Blogcast.

Everyone has heard about the Good-Better-Best product strategy. But not every company uses it. To be fair, it isn’t the right strategy for every company, but as a pricing advisor, I ALWAYS explore the possibility with my clients. It is extremely powerful.

Companies that adopt Good-Better-Best have higher win rates, higher Average Selling Prices (ASP), and higher Net Revenue Retention (NRR).

Before explaining how companies get all of these benefits, let’s look at how buyers make a purchase decision when facing Good-Better-Best. When you bought your cell phone, undoubtedly you chose from three levels of memory, Good-Better-Best. Let’s look at how decisions like that are generally made.

First, experts buy exactly what they need. Experts know what the features do and how they solve their problems, so they can make an informed decision. However, not many buyers are experts. They are not sure how they’ll be using their phone in a year, or what new applications they may need to run.

On the other hand, buyers who struggle to afford a mobile phone buy Good, the least expensive one. Wealthier buyers buy Best. Everyone else buys the one in the middle, Better. You probably bought the one in the middle. Most people do.

Here’s why: We are afraid to make a mistake. We are afraid that if we buy Good it won’t be good enough. If we buy Best we are wasting money. Hence, we buy the one in the middle.

But let’s look at a counter-example. When you put gas in your car, you likely have 3 choices of octane levels, Good-Better-Best. But in this case you probably don’t buy Better. Why? Because you are an “expert.” You have bought gas so many times over the years that you know what works best in your car. Or maybe you read the manual and follow the instructions. Regardless, you don’t fear making a mistake.

Fear of making a mistake will come up several more times in this article.

Now, buyer decision making with respect to Good-Better-Best in subscriptions is a little different. There, buyers like to subscribe to the Good package first. (They don’t want to make a mistake.) Then, if they like it and get enough value they may upgrade to Better or Best.

Benefits of Good-Better-Best

Every decision a company makes should be to grow profits. Good-Better-Best does that in three key areas: win rate, ASP, and NRR.

Higher Win Rate

Confused buyers don’t buy. Remember, they are afraid to make a mistake. They would rather not buy anything than make a mistake. This means if you have a complex price list, sell everything a la carte, or are fully customizable, there are some buyers (maybe many) who don’t buy from you simply because they are confused.

Instead, if you crafted a Good-Better-Best product offering, you make it easy for them to decide. They trust that you have experience in your field and created these packages to solve similar problems for similar companies.

Another interesting phenomenon is that with Good-Better-Best, you may actually dissuade buyers from looking at competitors. Buyers are reluctant to look at only one product and then buy. Why? Because they are afraid to make a mistake. So if you only have one product, they feel they have to compare it to something, a competitor’s product. But when you show them 3 products, they are now making a choice, which makes them more likely to make a decision without considering a competitor.

Higher ASP

Some companies have a single product they sell to everyone. To be effective, these companies tend to set low prices so they can attract the most buyers. However, some of their customers would have paid them a lot more. Good-Better-Best offers products at different price points so the buyers who get the most value will pay more for the best.

Good-Better-Best also gives salespeople a tool to help in negotiations. When a procurement person wants to buy Best, but asks for a discount, a great response is, “Oh, we have a product that can fit your budget. It’s called Better.” Good-Better-Best provides a tool to help avoid deep discounts in negotiations.

Higher NRR

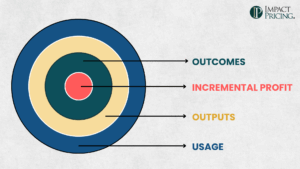

Subscription companies are often measured on Net Revenue Retention (NRR). This is the proportion of revenue they get this year from last year’s customers. Ideally, this is over 100%, meaning some of their customers pay more. One way to get customers to pay more is to upsell them. A subscriber buys into the Good level, and after using it, building trust, and experiencing value, they want to upgrade to Better. This only happens with a well-thought-out Good-Better-Best strategy.

To drive NRR, subscription companies must know when to emphasize perceived value vs experienced value. To win a new customer, buyers can only use perceived value. This is dependent on sales and marketing. To get a customer to upgrade, the subscription company must make sure the buyer experiences value. This is often done through effective onboarding and customer success departments.

Creating Good-Better-Best

Before defining your Good-Better-Best products, take a close look at your market segments. Although it’s possible to create Good-Better-Best for the masses, it’s much more effective when you build it for a specific market segment.

Mobile phones are a great example of Good-Better-Best for the masses. When you bought your last phone, you chose between small, medium, and large amounts of memory. This is a generic feature of a product targeted to almost everyone. This is better than a one-size fits all strategy, but it’s probably not optimal for your business.

Now, think about LinkedIn. They could sell the same product to everyone and offer small, medium, and large versions based on the number of connections or InMails. Instead, they defined four market segments: Recruiters, Salespeople, Job Seekers, and Professionals. Then, they created Good-Better-Best for each market segment. This is more powerful because the product portfolio closely represents what buyers want, simplifies the buyers’ decisions, and captures much more of their market’s willingness to pay. The price of the recruiter versions is much higher than that of the other versions.

Deciding which features go in which version (Good, Better, or Best) is challenging. Software companies have the advantage of relatively easily testing different versions. Hardware vendors probably need to think through this before building the products. However, companies like Tesla act like software companies by building one version of the hardware and enabling and disabling features using software.

The first rule of creating Good-Better-Best product versions is: buyers get more for more. No feature trade-off decisions. This means everything that’s in Good should be in Better, plus more. Best has everything in Better, plus more. You should never remove a feature someone may want when going from Good to Better or Better to Best. It makes the buyer’s decision harder which defeats one advantage of Good-Better-Best.

It’s easiest to think of creating the Good version first. Think of this version as almost a minimum viable product. You want it to be the least featured version of the product that still offers value and solves the main problem your product is built to solve. Then, price the good product close to the lowest price you are willing to accept. The goal of a good product is to win the price-sensitive customers but not make it too attractive to buyers with a higher willingness to pay.

Then define the Best version. It is almost everything you can do. Even if you don’t sell it at first, it’s like an advertisement on your capabilities. It shows your incredible competence. And of course, you want to price this high. You want buyers to see that you are a high quality vendor.

Last, define the Better version. It has the features that most people use. It is fully functional but without extra bells and whistles. You should expect most people to buy and use this version.

The best Good-Better-Best product lines have reasons behind each version, and that reason is in the name. For example, it’s common to see names like, “solopreneur, team, enterprise.” Naming the versions based on who they best fit or what problems they solve makes it easier for buyers to understand why you’ve crafted this portfolio and to make their purchase decisions.

Finally, the price of the Better package will influence which of the three options your buyer chooses. The most common use of Good-Better-Best is to sell more of the Better, so expect 50% or more of your sales in Better. Start about halfway between Good and Best. Then, tweak your price up or down to move the mix and try to get 50% or more of your sales in Better.

There is a different pricing strategy called the Decoy Effect. As the Better price increases and gets closer to the Best price, more people will choose Best. The Decoy Effect is when you make it very near or even equal to the Best price. Best is obviously much better than Better, but almost the same price, so most people will choose Best. Remember, they don’t want to make a mistake, and in this situation, buying Best is not a mistake because the decision is obvious.

Even after crafting a Good-Better-Best product line, you may still have some optional features. Options should be uncorrelated with Good-Better-Best. Otherwise, you would just put them in one of the Good-Better-Best versions. Also, options should be expensive. You don’t want to manage a lot of SKU’s, and you definitely don’t want to complicate the buyer’s decision.

Selling Good-Better-Best

Communicating Good-Better-Best options has a few nuances. If you have a direct sales force who presents your product options to a potential buyer, then present the Best first. Explain the value of the most important capabilities of the complete product. Then, tell the buyer which features you eliminate for the lower-price versions. When you do this, buyers will tend to buy higher-end versions. Here is why that works.

Prospect theory tells us that losses loom larger than gains. People tend to dislike losses about twice as much as they like gains. But whether something is a loss or a gain depends on how it’s framed. When you start by describing the fully featured Best version, buyers use that as the base. Then, as you take features away, they are interpreted as a loss. The lower price is interpreted as a gain. According to prospect theory, the presentation technique influences buyers to overvalue the feature and undervalue the price.

If you present the Good version first, they use that as the base. Then, when you describe Better, they consider the additional features as gains and the increased price as a loss. This influences them to overvalue the price and undervalue the features.

The same strategy works with free trials. Let people try every feature during the trial period. Then, taking away features feels like a loss.

However, if you put your pricing and packaging on your website, present Good-Better-Best from left to right. It is what your buyers expect to see. Anything else makes you look less trustworthy.

I’m sure there are many more nuances to Good-Better-Best not mentioned in this article, but hopefully this will motivate you to take a look at how you can implement a Good-Better-Best strategy. It’s not easy, but it is powerful. Let us know if you want some help.

Share your comments on the LinkedIn post.

Tags: good better best, pricing, pricing skills, pricing strategy, revenue, value

Tags: good better best, pricing, pricing skills, pricing strategy, revenue, value