You can listen to the full audio version of this blog we call — Blogcast.

A pricing metric is really the intersection of two perspectives: how the buyer measures value (their KPIs) and what the seller can and does measure in terms of usage. The closer the pricing metric aligns to the buyer’s KPI, the more natural and fair the pricing will feel.

The fundamentals of pricing metrics have not changed with the advent of AI, but the choices we make may look different because AI shifts usage patterns, introduces significant operating costs, and opens new possibilities.

Why Pricing Metrics Matter

Metrics shape the buying experience as much as the actual price. Buyers don’t just ask, “How much does it cost?” They also want to know, “What am I paying for?” The unit of measure we select can determine if the way a buyer pays feels fair, predictable, and aligned with the value they receive.

- Fairness and trust: Buyers judge fairness more by the metric than by the absolute price. An AI vendor charging “per token” may sound unfair or confusing, even at a low price, while “per case resolved” feels naturally aligned with value.

- Comprehension: If buyers don’t understand the metric, they hesitate to buy. Pricing that requires an engineering degree to decode will not scale.

- Predictability: For buyers, metrics determine whether budgets can be planned. For sellers, they determine whether revenue is stable or volatile.

- Growth and expansion: Metrics can create natural upgrade paths. Seat-based pricing, for example, grows as a team expands. Usage-based metrics grow as adoption increases.

- Profitability: In SaaS, costs were near zero and often ignored. In AI, operating costs are significant. Metrics must balance buyer value with protecting margin.

The wrong metric can destroy willingness to pay, even when price levels are reasonable. A confusing or unfair metric creates friction that no amount of discounting can overcome.

The Three Metrics Framework

WHat we’re talking about here is really three related but distinct concepts:

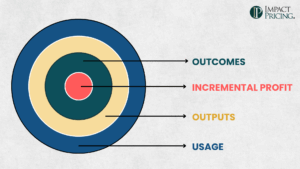

- Value Metric: This is how the buyer measures value. These are essentially the customer’s KPIs. In B2B, the ultimate value metric is incremental profit. But buyers often see value through more specific drivers such as cases resolved, new sales generated, fraud prevented, or hours saved.

- Usage Metric: Observable (and measurable) units of consumption that correlate the product’s usage.. Examples include seats, transactions, gigabytes, API calls, or tokens. Seat-based pricing is simply one type of usage metric.

- Pricing Metric: What shows up on the invoice. This is the unit the company decides to charge for.

Ideally, the pricing metric is the value metric. That is outcome-based pricing, charging for the measurable results the solution delivers. But most often, value is hard to measure directly, or attribution is disputed. In those cases, companies fall back on usage metrics that are strongly correlated with the value metric and use those as the pricing metric.

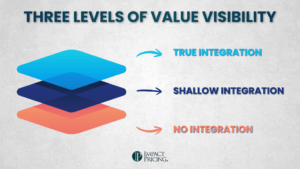

Think of this as a ladder:

- Start with the customer’s KPIs, the value metrics.

- Identify usage metrics that correlate with them and that the seller can meter.

- Select the pricing metric that best balances correlation to value, buyer comprehension, predictability, and profitability.

Examples:

- A support automation agent:

- Value metric: cases resolved

Usage metric: number of cases handled, conversations completed - Pricing metric: per case resolved, or a monthly bundle of conversations

- Value metric: cases resolved

- A sales acceleration tool:

- Value metric: incremental revenue (or margin) from new sales

- Usage metric: number of qualified leads delivered, proposals generated

- Pricing metric: per qualified lead, or subscription plus per-lead fee

- A developer API:

- Value metric: time saved and reliability

- Usage metric: API calls, tokens processed

- Pricing metric: credits mapped to calls or tokens for predictability

It is also critical to remember that pricing metrics live in the problem scope layer of the Value Architecture, which means they only make sense inside a market segment. A metric that feels natural in one segment may not work at all in another, even for the same product.

For example:

- Dropbox used different metrics for different segments. In the consumer market, they price by gigabytes of storage, a usage metric tied to individual needs. In the business market, they price per seat, because collaboration and team size are the relevant drivers of value.

- Salesforce also adapts by segment. Sales Cloud often uses per-seat pricing, because sales reps are the natural unit of value. Marketing Cloud prices by number of contacts or messages sent, because that aligns with marketer KPIs.

In other words, pricing metrics are not universal. They work best when tailored to a specific segment, reflecting that segment’s value metric and linking it to a usage metric the seller can measure.

The AI Challenge: Familiar Metrics in a New Context

In SaaS, per-seat pricing became dominant, and it still is. It was simple, predictable, and easy to understand. Usage, transactions, and even outcome-based models all coexisted. AI is not inventing new logic. It is simply reshuffling which metrics make the most sense today.

- Seats break down: AI often reduces the number of people needed. A support agent powered by AI might replace 10 human agents. Charging per seat collapses revenue even as value rises.

- Tokens emerge: Tokens are a usage metric tied to cost. They make sense for developers but feel meaningless to business buyers. Tokens are cost-plus, not value-based.

- Outcomes beckon: Outcome-based pricing is the holy grail, charging per case resolved, per fraud prevented, or per dollar of cost savings. It ties directly to the value metric. But attribution, trust, and risk-sharing make it difficult in practice. FinAI is a strong example of outcome-based pricing.

- Usage remains practical: Usage metrics that correlate with value are often the safest proxy. Calls handled, invoices processed, or leads delivered all make sense as usage-based pricing metrics when direct outcomes are harder to measure.

The variety of experiments happening today illustrates the point. Sam Altman at OpenAI chose what seemed like a “random” number, $200 per month for advanced ChatGPT features, while still offering free and $20 versions. Microsoft sells Copilot as an add-on subscription to Office, keeping the familiar seat-based model but charging a premium for AI capabilities.

Metrics are as central to pricing AI as packaging. The fundamentals have not changed, but the metrics that dominate are shifting. Seat-based pricing does not work well for many AI products, but usage, tokens, and outcomes all have roles to play, each with trade-offs. We will dive deeper into these in future blogs.

Share your comments on the LinkedIn post.

Now, go make an impact!

Tags: ai pricing, pricing, Pricing AI, pricing metrics, pricing skills

Tags: ai pricing, pricing, Pricing AI, pricing metrics, pricing skills